Operation Manna and Operation Chowhound were humanitarian food drops to relieve the famine in Holland behind Nazi lines late in World War two. 20,000 people had died from starvation and 980,000 were malnourished. Many had survived by eating pets and spoiled food. Some even eating tulip bulbs leading to poisoning.

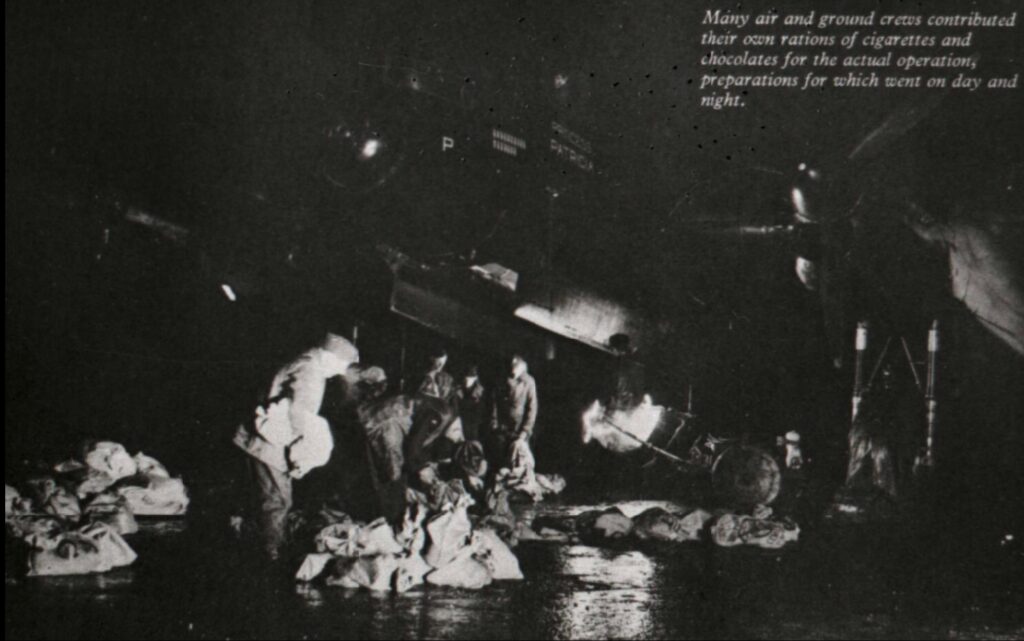

Loading food packed in double hessian sacks

These food drops were completed by International Bomber Command crews,(29 April – 7 May 1945), who dropped 7,000 tonnes of food into the still Nazi-occupied western part of Holland. This was carried out by squadrons from many nations and many squadrons of mixed nationality reflecting the International make up of Bomber Command in World War two, flying from multiple airfields in England to the drop zones in the western Netherlands. The food had to all be packed into doubled up hessian sacks a very difficult task carried out by the Royal Army Service Corps and an all hands on deck approach.

Operation Chowhound (1–8 May 1945) the United States Airforce dropped 4,000 tonnes of food. In total, over 11,000 tonnes of food were dropped over the 10 days, to help feed Dutch civilians in danger of starvation by operation Manna and operation Chowhound.

By early 1945, the situation was growing desperate for the three million or more Dutch people still under Nazi occupation. Prince Bernhard appealed directly to Allied Supreme Commander Dwight Eisenhower, but Eisenhower did not have the authority to negotiate a truce with the Germans.

So prince sought permission from British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and U.S. President Franklin D Roosevelt. On the 23rd of April, authorisation was given.

The Operation Manna Radio Broadcasts

Survivors tell of how important it was to hear these messages as hope was restored for them, and of the excitement that help was coming. Radios were not allowed for the Dutch people but many had them to secretly listen to the BBC or Radio Resurgent Netherlands. Not knowing who to trust the news they heard was often kept a secret within their families.

On April the 24th the Dutch people received a radio broadcast that food drops are about to begin from the Allies and any Nazi intervention would be considered a war crime.

On April the 25th the Dutch people receive a broadcast that the German Military Commander agreed to the supply of food but not by air as had been suggested.

On April the 26th the German Governor Seyss Inquart agrees under pressure to the food drops by air and the Dutch people are informed by radio broadcast.

(April 27th the Bomber Command planes are grounded by bad weather)

On April 29th at 8.00am the Dutch People are informed by the “Voice of Freedom Radio Resurgent Netherlands” that planes would come and drop flares today and other planes would drop food.

On April the 29th at 12.10pm they are informed by another broadcast that the planes had left the UK and were on their way.

Operation Manna was in Full Swing but still with no formal agreement in place a huge risk flying a such a low height.

A formal agreement was shortly put into place that aircraft would not be fired upon in specified air corridors.

The International Bomber Command operation started first. It was named after the food which was miraculously provided to the Israelites in the book of Exodus MANNA.

The first of the two International Bomber Command Lancasters chosen for the test flight, on the morning of 29th April 1945, was nicknamed Bad Penny, as in the expression “a bad penny always turns up”. This Lancaster with a crew of seven (five from Ontario, Canada, including pilot Robert Upcott took off despite the fact that the Germans had not yet agreed to a ceasefire. (Seyss-Inquart would do so the next day.) Bad Penny had to fly low, down to 50 feet (15 m), over German guns, but succeeded in dropping her cargo and returning to England.

International Bomber Command aircraft from 1 Group, 3 Group and 8 Group took part, with 145 drops by Mosquitoes and 3,156 by Lancaster bombers.

The operation was performed at a height of 490 ft (150 m), some even flying as low as 390 ft (120 m), as the cargo did not have parachutes. The drop zones, marked by Mosquitoes from 105 and 109 Squadrons. 7000 tonnes of food were delivered.

John Funnell, a navigator said:

As we arrived people had gathered already and were waving flags, making signs, etc., doing whatever they could. It was a marvellous sight. As time went on, so there were also messages, such as Thank you for coming boys. On the April 24th, we were on battle order at Elsham Wolds. We went to a briefing and were told the operation was cancelled because it was thought it was too dangerous for the crews. The idea was we would cross the Dutch border at 1,000 feet, and then drop down to 500 feet at 90 knots which was just above stalling speed.

On the 29th, we were on battle orders again. There was no truce at that point, and as we crossed the coast, we could see the anti-aircraft guns following us about. We were then meant to rise up to 1,000 feet, but because of the anti-aircraft guns we went down to rooftop level. By the time they sighted on us, we were out of sight. A lot of people were surprised we went without armaments, in case of any trigger-happy tail gunner.

Originally, it was going to be ‘Operation Spam’ which was in my logbook.

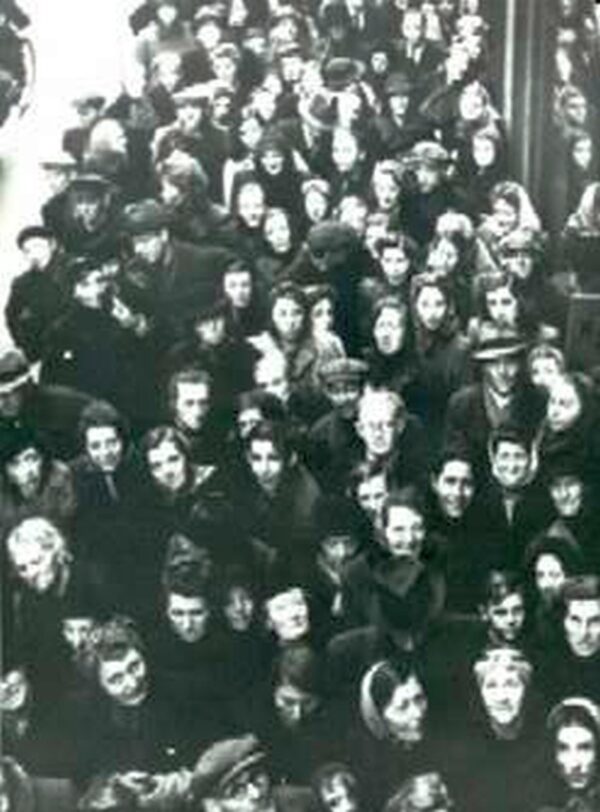

The idea was for people to gather and redistribute the food, but some could not resist eating immediately. This led to instances of illness, vomiting, and, in some cases, death. These outcomes are due to Refeeding Syndrome, a condition that occurs when an individual suffering from starvation eats high-fat foods too quickly. On the other hand, distribution sometimes took as long as ten days, resulting in some getting the food only after the liberation. Many lives were saved, and it gave hope and the feeling that the war would soon be over.

Three Bomber Command aircraft were lost two in a collision and one due to engine fire. Bullet holes were discovered in several aircraft upon their return, presumably the result of being fired upon by German soldiers who were unaware of, or violating, the ceasefire. Three 8th Airforce aircraft were lost one of these from rouge fire from the ground causing an engine fire. Sad losses so near to the end of the War.

On the American side with Operation Chowhound, ten bomb groups of the US Third Air Division flew 2,268 sorties beginning 1 May, delivering a total of 4000 tonnes of food.

Transporting food away from a drop Zone

On May 2nd the ground-based operation “Faust” began. It is estimated that the air and ground operations saved a Million Dutch people from starvation.

Operation Chowhound

This was the US aerial counterpart of operation Manna.

Operation Chowhound, lasted from 1 May 1945 to 8 May 1945. A total of 2,268 sorties were flown by B-17 Flying Fortress bombers, delivering about 4,000 tons of food, some of which was in the form of K-rations.

The operation followed the same pattern as operation Manna although flown by ten bomb groups of the US Third Air Division from airfields further south in the UK than the Bomber Command ones.

Henry Cervantes of 100th Bomb Group Thorpe Abbots said:

“The agreement with the German area commander required that we stay under 500-feet, remain within strictly mandated corridors, and not carry gunners aboard our B-17s. No one felt any better when our pre-mission briefer added, “Anyone fired upon will receive credit for a combat mission.” The modified bomb bays were loaded with boxes of ten-in-one rations and on May 3rd we flew our first mission.

We went in at wave-top level, hopped over the dykes, and skimmed by telephone poles in an effort to stay as low as possible. German flaks batteries where everywhere and we kept a wary eye at the gunners who squinted at us like duck hunters waiting for the season to open.

Early May is tulip time in Holland and despite the ugly scars of war, carpets of blazing colors dotted the countryside. Joyful women and children were everywhere. Some waved American and Dutch flags at us while others pointed to messages in open fields that read, “Thank You Boys,” and the like.

Near Amsterdam we “bombed” an open field centered with a white cross that appeared to be fashioned from bed sheets. Below us, it was a free-for-all as civilians with German soldiers among them could be seen scrambling for boxes as even more of the 50-pound missiles showered down. On May 5th, we repeated our performance over Bergen and were again treated to the heartwarming sight of mothers hugging their children as they pointed to the big grins on our faces.”

Although, I flew 26 combat missions over Germany, among all of my wartime experiences those three missions are among my most treasured memories.

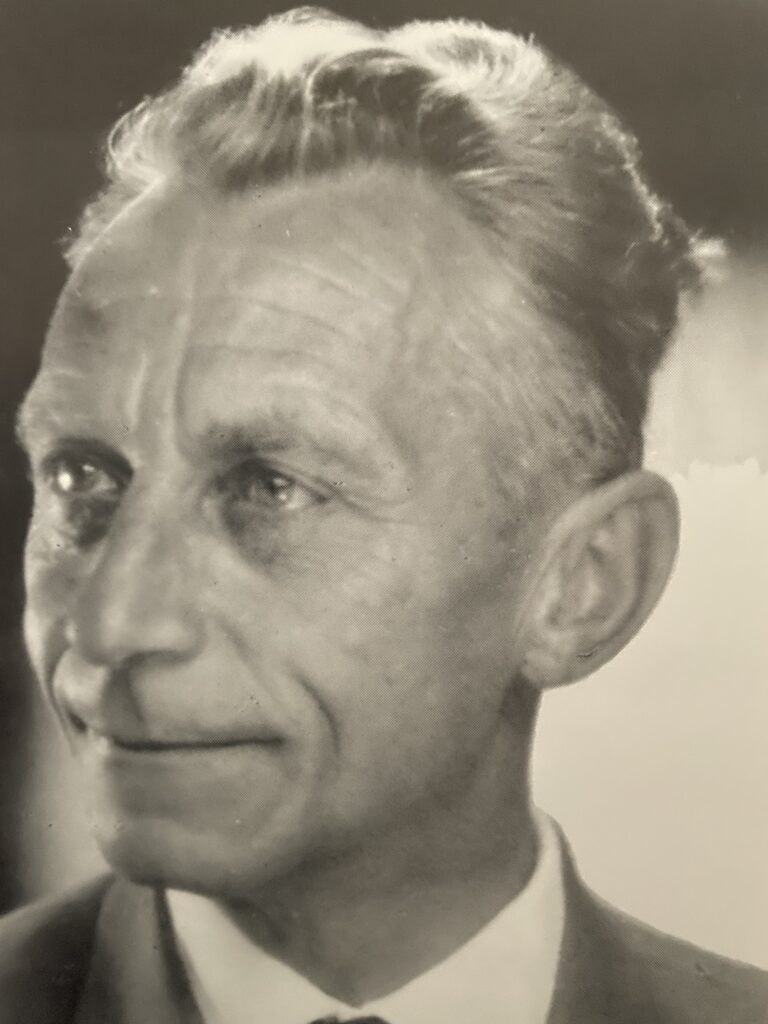

Mhr Van der Wal

Mhr Van der Wal was a hugely important part of operation Manna and operation Chowhound. Before the War he was involved in the export of Dutch potatoes. Once Holland was occupied by the Nazi forces he was placed in charge of potato distribution within Holland. He used the needed documents and transport for potato distribution to move supplies for the resistance and the movement of aircrew evading capture.

Mhr Van der Wal organised the collection of equipment dropped by the RAF and its distribution to the resistance. So naturally he was turned to organise the distribution of the food dropped by operation Manna and operation Chowhound.

With his unique position was able to ensure the fair distribution of food to a population on the verge of starvation. Without Mhr Van der Wal operations Manna and Chowhound would not have been as successful as they were. Many Allied aircrew and Dutch Civilians owe their lives to his work.

Pieter van Marken a Dutch teenager at the time said:

“After the so called “Hunger winter” of 1944 – 1945 when some 20.000 people died of starvation in Western Holland, the Allies sent in planes. The Americans, the 8th Air force, sent hundreds of B-17 bombers, and R.A.F. Bomber Command, sent hundreds of Avro Lancasters to drop food at Schiphol, and also a great number of other “dropping zones” in still occupied Western Holland.

I “helped”, collecting the food and I had positioned myself on a barge in the canal – the “Ringvaart” – adjoining the airfield.. Others came to off load the sacks of food they had collected on the fields and runways, loaded on primitive vehicles. I helped off load the sacks into the barge. I remember the tins of butter, burst open and the sacks of sugar and broken tins of bacon.

Dipping my fingers into the butter and the sugar, I gorged myself on this as well as scooping and eating the bacon out of the broken tins. Everybody else did the same thing. Gorgeous. The RAF had dropped tins of hard biscuits – emergency rations – and tins of corned – “bully” – beef. I came to love corned beef. Everything was subsequently distributed. Soon after, we also got rationing tickets to collect so called “Swedish bread”, bread made from Swedish flour.

Originally I thought that the loaves had also been dropped by air but it is only recently that I found out that the bread was made from the flour, the Swedes had sent by ship. Beautiful white loaves. We also got margarine to go with it. You can’t imagine what a glorious taste a slice of that white bread and margarine had. You had to stand in a long queue at the bakery shop to collect your bread rations. But you didn’t mind. Thank you again, Sweden.

For us liberation came on May 6, 1945. One day after the formal capitulation by the Germans. The food droppings continued for some time. Road transport followed; to bring more food and Rotterdam was again open for shipping.”

The images below showing drop zone November in 1945 where our friends in the Netherlands have set up their station.