Manna: A Bombardment of food and freedom!

A brochure produced in a modern day Netherlands town explaning operation Manna to younger people translated into English.

© 2006 Historical committee residents’ organization Terbregge ‘s Belang

The distribution of this brochure

to tenants in Nieuw Terbregge was made possible in part thanks to Woningstichting PWS Rotterdam.

Foreword

This brochure was created to inform people of today about the events of the past. Food drops took at the

end of World War II in the area where the residential area of Nieuw Terbregge has been built since the late

1990s. Thanks to these drops, many hundreds of thousands of people in the west of the Netherlands could

be saved from imminent famine.

In order to keep the memories of these drops alive, a monument has been erected on the spot where in 1945 the first

Lancaster’s flew up the to dropping site with their life-carrying cargo. This unique monument, which does

not commemorate the heroic deeds of resistance fighters or those who died for our freedom, symbolizes

the fact that many British, Americans and Poles worked for the starving Netherlands in 1945.

It was Henk Dijkxhoorn, chairman of the historical committee of Terbregge’s Belang who called attention

to this almost forgotten period at the end of World War II. He spoke with pilots who participated in these

drops; he visited them in England and in the United States. He made the memories of the food drops in

Terbregge come alive. This brochure should therefore be seen as an addition to Henk Dijkxhoorn’s efforts

for the realization of the monument and a lasting souvenir of Operation Manna.

Tom Janse,

June 2006.

The Hunger Winter

Although with the invasion of Normandy and the subsequent Ardennes Offensive, the hope for a quick

liberation of the Netherlands was growing, nothing could be further from the truth. On Crazy Tuesday

(September 5, 1944), many still took to the streets , dressed in orange and red-white-and-blue, appearing out of

to welcome the liberators. However, they did not come yet.

Hopes of liberation were soon dashed in the western part of the Netherlands. It would take many harsh

months before the first allies drove through the streets.

The Allies had not been able to liberate the entire area at once. They were afraid that as the Germans had added force to their retreat by blowing up dikes and sluices, causing a large part of the country to be flooded. The number of casualties among the civilian population would then have been incalculable. Also, the resistance groups were too weak to efficiently assist the Allied forces. The area was densely populated with four million inhabitants, which meant that the battle would claim many victims.

Because liberation of the Netherlands would be too high risks, the American and British Supreme Allied Command focused on taking Germany as quickly as possible.

However, the food situation in the western part of the Netherlands became increasingly dire. On

December 4, 1944, bread rations were reduced. This date marked the beginning of the hunger winter. No more food was brought in. Food shipments across the IJsselmeer had also come to a halt. The hunger winter was a fact.

The hunger winter refers to the period between October 1944 and April 1945, when there was insufficient food in the occupied western part of the Netherlands.

Over 20,000 people died of malnutrition and cold in that disastrous winter~

By October 1944, people in the major cities of the Western Netherlands were already living on a starvation ration:

1 loaf of bread and 1 kilogram of potatoes per person per week. This is not much, but it still requires a

supply of 25,000 tons of grain per month. From the beginning of November 1944 to the beginning of

December, however, only 9,000 tons were transported. Thus the catastrophe announced itself.

Tulip bulbs

On pamphlets from the National Food Administration in February 1945, we read the following recipe for

preparing flower bulbs:

Peel the tulip bulbs, cut them in half and remove the yellow sprout. Remove hard and lite particles.

Soup of tulip bulbs

1 litre of water, 1 onion, 4 to 6 tulip bulbs, aroma, salt, 1 teaspoon oil, curry surrogate. Chop the onion and

fry the curry surrogate lightly brown with the oils. Add the water and aroma. Bring the soup to a boil.

Grate the cleaned tulip bulbs over the boiling liquid.

Cook this under stirring for a few more minutes and finish to taste with some salt.

Insufficient food

The reasons why there was insufficient food :

- The general railroad strike ordered by the government in London. The government-in-exile thus

wanted to prevent the Germans from sending reinforcements to the western Netherlands; - In response to the railroad strike, the Germans banned transportation of food and fuel by inland

waterway. - The harsh winter froze the rivers and canals, making water transportation virtually impossible even

after Prohibition was lifted; Even if trains ran and ships sailed, the Netherlands was torn apart by war.

The chance of Allied bombing was high and a number of rivers, such as the Waal near Nijmegen, were part

of the front line.

The hunger winter mainly affected the western Netherlands, because in the occupied northern and

eastern Netherlands there were many farms where food was plentiful. The southern Netherlands had

already been liberated and also had no food shortages. Moreover, people in those areas were much more

self-sufficient. For example, they knew how to preserve food for a long time, for example by macerating

it, and how to bake bread. - Last but not least, far fewer people lived there than in the urbanized West.

For the hundreds of thousands of residents of the large cities in the western part of the Netherlands,

there were a barely adequate ways to get food:- The NSB government tried to distribute the little food

equitably by setting up soup kitchens;- In the countryside, food was available and long lines of people

went on foot or with handcarts to farms to food. These treks, very dangerous because of cold and war,

are known as the hunger treks; - The inhabitants of the western Netherlands supplemented their meagre diet with rose hips, tulip

bulbs, sugar beets and even dogs and cats

Air Commodore Andrew James Wray Geddes

We pay special attention in this brochure to Air Commodore A.J.W. Geddes. He had an important part in

the preparations for and negotiations of Operation Manna.

That the food shortage in the western Netherlands would end in a humanitarian disaster of great

proportions is clear from the above. Geddes was ordered to come to General Eisenhower’s headquarters in

Reims on April 17, 1945 for an urgent mission. There General Walter Bedell-Smith, Eisenhower’s Chief of

Staff told him the following:

“The Dutch are starving, their food is running out and the Germans can no longer feed them. The Dutch

government, the President and Churchill are on us. Something must be done to bring this to a

speedy end. I want to see a plan from you to feed 3,500,000 people by air. I want dropping fields,

corridors, everything. I will give you every support. Bert Harris is ordered to provide two Bomb Groups and

enough Pathfinders. The Eighth Air Force will provide three Bomb Wings. We must present the Krauts with

a complete plan, not a negotiated plan.

Do it Geddes, and do it quickly. If you need help, you come to me. I’ll make sure Ike

(Eisenhower) has your back. We’ve cleared a room here for you at SHAEF. Tell me what and who you need and I’ll make sure you get it. Thank you, So much for Geddes’ .

The plan had to simple in concept, it had to executed like a bombing raid, targets had to be chosen, rules drawn up. Crews had to be informed of it.

Negotiations

Allied leaders had come to the realization that waiting longer to provide food aid could lead to great catastrophes.

Plans to bring in supplies by air dated as far back as mid-March 1945. This plan under the code name Placket-C assumed a supply of 2,200 tons of food. Millions of rations actually intended for liberated prisoners of war could be released for dropping over western Holland. However, the plan had a weak side:

It was assumed that the Germans would offer no resistance.

Meanwhile, in Brabant, the first contact between occupied territory and Allies had been established.

Following the Committee of Confidential Officers, Van der Gaag and Neher had broken through the lines

and arrived in the south. After informing Prince Bernhard of the plight, they left for London to inform

Prime Minister Gerbrandy.

They told that the Germans were willing to talk about the supply of food:

For example, the Germans promised that they would suspend all destruction, carrying out death sentences, treat

political prisoners better and stop actions against the resistance. It seemed too good to be true.

On April 14, Prince Bernhard went to Reims to discuss with General Eisenhower what the Allied

response would be. In London, Gerbrandy consulted with Churchill. After mediation by South African

Prime Minister Smuts, he was prepared to give permission for direct negotiations with the Germans.

At 7 p.m. on April 26, Herrijzend Nederland reported:

“The German military commander in Holland agrees in principle to the plan to bring food to occupied

Holland. However, he does not agree to supply by air , because he is afraid that the pilots can see his

defences”

The same day, however, a message went from Holland to London: Seyss-Inquart had expressed his

willingness to consider any proposals regarding food aid.

Seyss-Inquart had a letter delivered to the contact man of the College of Confidential Officers in which he accepts, after consultation with General Blaskowitz, four drop-off sites in the area Leiden – den Haag –

Rotterdam: Renbaan Duindigt and the airfields Ypenburg, Valkenburg and Waalhaven.

He set the condition that west of the line Zaandam Aalsmeer – Gouda – Dordrecht the Allied air force should not engage in any other activity. To avoid making the Germans suspicious, the Dutch authorities in The Hague and London urge the Allies to determine the detailed arrangements for the drops in close consultation with Seyss-Inquart in order to spare him as much “loss of face” as possible.

All preparations for the drops had begun in England a week earlier. In February there had already been tests and it

demonstrated that dropping bags of food was possible if the planes adhered to a set speed, altitude and

position of the wing flaps.

On April 28, the green light came. The second delegations were to meet in Achterveld, Gelderland.

The Germans, still not reassured that help would come and no bombs, decided to be prepared for all eventualities, such as landings of paratroopers, planes and weapons.

Among the Allied delegation was Air Commodore Andrew Geddes. He was accompanied by Major

General Sir Francis de Guingad, Montgomery’s chief of staff. Geddes had with him a list of sun 104

possible dropping zones.

The German delegation consisted of four men, Dr. ErnstSchwebel, Reichsrichter, Dr. Plutzar, Hauptmann

Dr. Stoeckle and Oberleutnant Von Massow.

Dr. Schwebel, however, did not have the mandate to make arrangements for food supplies.

The Reich Com- missionary had sent him to make preparations for a meeting between Seyss-Inquart and General Eisenhower or his representative.

On April 30, they would meet again to agree on plans. In this last conversation, the Germans stated that

they would do everything they could to provide the necessary assistance in immediately resupplying the Dutch, unless it would result in Allied forces entering or flying over undefended areas.

General Bedel Smith, head of the allied delegation named the three most important conditions

which the experts had to include in their plans:

- Aerial drops would on a large scale.

- Dutch distribution capabilities did not allow for ejection in more than ten locations. Nor could they

monitor and distribute supplies that were ejected at night. - Supplies would be brought in by sea through certain ports;

Inland waterways from Hollands Diep to Rotterdam, from Arnhem to Utrecht and from Kam- pen to

Amsterdam would be used,

So that ships could count on waterways were to be cleared of mines.

While negotiations continued in Achterveld, people in England were ready to begin the “best operation

ever flown”.

At 12:10 a.m. on April 29, it sounded through the airwaves: ‘the BBC reported that the first

planes with food for occupied Holland had taken off. ‘Already in the morning planes had taken off that

would mark the dropping places with coloured flares.

Even before the negotiations had ended, the Allies had a final decision. Masses of Dutch people who had heard the good news left their homes to see with their own eyes. Operation Manna had begun!

The food drops

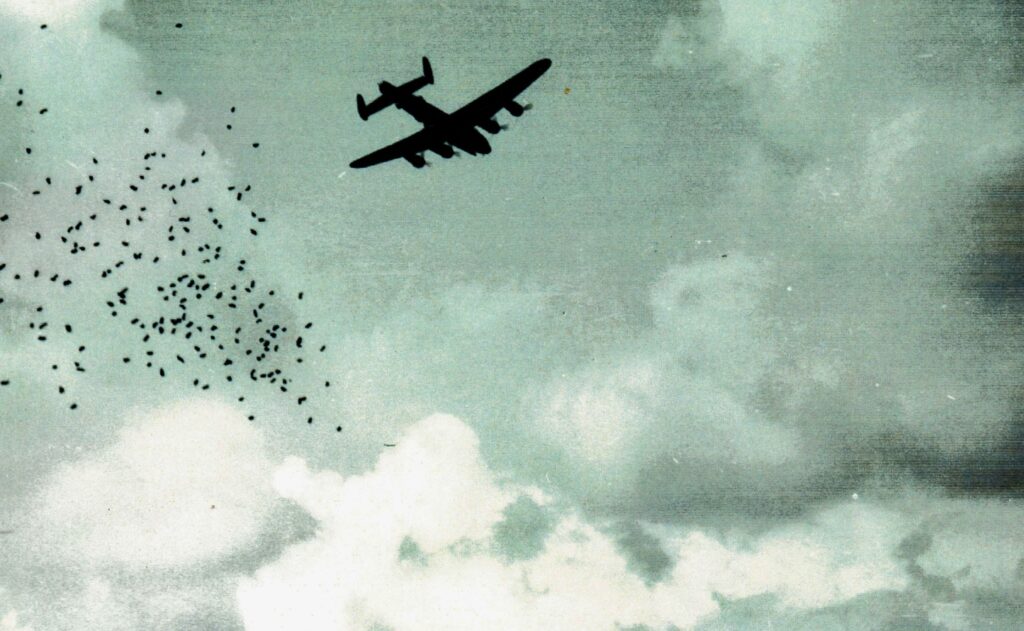

Under the operational names Manna (Great

Britain) and Chowhound (USA – freely translated, chowhound means grease bag), 5,500 flights were

conducted on the western Netherlands in the period from April 28 to May 10, 1945.

The bomb bays of British Lancasters and American B-17s now contained not bombs, but cans and bags of food: from

cookies, flour and margarine to egg powder and corn beef.

After months of consultation between the Allies and the Germans, during the famine winter, on 29 April1 945 the first food drop for starving Western Netherlands was carried out.

Operation Manna would last a total of eight days.

Among others, the 625th squadron in Scampton (Lincolnshire), the (Australian) 460th, 467th, 100th and 101st squadrons of the RAF. The 300th (Polish) squadron was also present at these drops. In all, more than 30 British squadrons and 11 Bomb Groups of the U.S. Air Force were involved in these drops.

On the first mission, 242 Lancaster-type heavy bombers flew to the Dutch coast via an agreed corridor. On April 29, 1945, 535 tons of food was dropped by the RAF. The Germans had agreed with the Allies that these bombers were allowed to drop the food and emergency rations at low altitudes. To ensure that no paratroopers were dropped from these aircraft during this armistice, the German Supreme Command secretly ordered the contraction of FLAK anti-aircraft guns. Also, the German SD would take spot checks to determine whether these dropped shipments were indeed food and not illegal weapons shipments.

Some bombers were nevertheless shot at by the Germans (with light small arms fire) during these flights.

However, they were able to shed their packages without too much trouble.

At ten past one on April 29, English Lancaster’s skim at an altitude of one hundred and fifty meters above about the ten drop places.

‘No one is inside anymore,’ writes the then 17-year-old A. de Jong from

Vlaardin-gene in his diary. Cheering shouts and waving flags, a frenzied crowd watches packets of food fall from the sky.

De Jong now: “That was such a wonderful thing. I lived in a place from- where I a view over the farmlands as far as Hoek van Holland. There I saw all those packages coming . A beautiful sight.”

In the meantime, the USA Air Force also had the go ahead. Due to bad weather, however, they could not join the operation, which they called Operation Chowhound, until later. On May 1, 1945, more than 400 American B-17 bombers headed up from England toward Holland. From now on, the Americans and British worked together and, as a result, they doubled the number of food drops.

This increased the number of dropping zones from five to eleven. After 1 May 1945, the RAF and USAAF had their own zones. The zones

for the RAF were: Valkenburg, Duindigt, Ypenburg, Terbregge, and Gouda.

The USAAF had the following zones: Schiphol Airport, Vogelenzang, Bergen, Hilversum, and Utrecht. More than 11,000 tons of supplies

were dropped over occupied Dutch territory in these eight days. Bomber Command carried out 3100

flights and the USAAF 2200. For the population, the worst suffering was then over.

On May 8, the bombers took to the air for the last time to rain food from the sky. Meanwhile, the

German capitulation was a fact and gradually the much larger transports of food by road could take over

the supply.

A total of 2,200 flights were by flying Fortresses, dropping 5,100 tons.

The British made 3,156 sorties with their Lancaster’s (also called Flying Grocers), 6,684 tons of food,

assisted by 145 mosquito flights to mark the dropping grounds.

Operation “Manna” was at an end. Almost 12,000 tons of food had been delivered in the fastest way possible.

And on top of that, the sight of this grandiose air operation had given the Dutch in the still newly

occupied area a great kick. If this was possible, then liberation should no longer be far off.

And fortunately, that turned out to be all too true.

The food drops were distributed to various drop-off areas:

Terbregge 3656 tons

Schiphol 1982 tons

Ypenburg 1554 tons

Utrecht 455 tons

and Valkenburg 871 tons.

Even near a city like Hilversum, 148 ton were dropped. A series of small drops occurred near

places like Alkmaar, Baarn and Haamstede. The total of these relatively small transports amounted to 18 tons.

Furthermore, food was also brought in by road by the Canadian Army under the operational name

Faust and via the major rivers, along the Nieuwe Waterweg and the IJsselmeer.

Drop zone Terbregge

The first choice to supply Rotterdam with food by air was the Waalhaven. However, the Germans were

unable to all the land mines they had placed there on short notice.

By mistake, the first day (29) was still dropped over Waalhaven, but this mistake was quickly

corrected. By the way, most of the packages there had not fallen onto the former airfield, but into the

water of the Waalhaven. A number of packages could still be retrieved above water there.

Terbregge was certainly not the most attractive location where food could be dropped:

The area, bounded by Terbregseweg, Bergse Linker Rottekade and Stoopweg/spoorbaan was particularly marshy,

especially because of the much rain that had fallen in the weeks leading up to the food drop; in addition

every forty meters the meadows were cut by ditches. The terrain in the Alexander polder was 6.55 meters

below sea level.

Only a few places could be reached by horse and cart, and then only with wagons with thick rubber tires.

It was clear that Terbregge was not the most fortunate place to dispose of food:

There was damage by fire and water; a collector was hit by a food parcel and died instantly. Several packets landed on houses

on Terbregseweg and caused a lot of damage. About five houses burned down when flares from the

Pathfinders landed on the roofs. Some sheds also burned down completely.

The Rotterdam Manna Committee which included: Mayor Miller, Beauftragte Völckers, Alderman of General Affairs Duithuis, the secretary of Beauftrage Mayer, Ernahrungsreferent Chur and verbin- dings officer Hofell Mayer immediately realized that this terrain would cause enormous problems with the collection and transport of the food.

Nevertheless, the Technical Department of the Municipality of Rotterdam thought they could make some improvements.

Workers laid steel plates over a total length of more than 2,000 meters. This at least created makeshift drainage routes.

Despite all the difficulties and extremely little cooperation from the German side, the Rotterdam Manna Committee set to work energetically. The organization necessary to make the logistics of the food possible on the ground was set up in two days. Two ground commanders were appointed with one assistant each.

The commanders were responsible for the entire drop- ping zone and their assistants were tasked with receiving the food.

Mr. Derksen was to supervise the site with the help of the CCD, the Crisis Control Service.

The Rotterdam municipal police also provided manpower. Workers and means of transportation were by Rotterdam

companies, from the Heineken and Oranjeboom Brou- werijen. Initially, contact with the Germans was rather difficult. The roads were under the control of the Germans and the Dutch police. Beauftragte Völckers had stipulated that no one should be admitted to the grounds unless in possession of a certificate issued by the Beauftragte.

This did not work. The police complained that the Germans were driving around with Wehrmacht cars that were not allowed to be checked by the police. The Germans in turn accused the police officers of theft.

Völckers, after consulting with the president of the court and the district attorney, decided to withdraw

the German militia. Court officials took their place.

The Luftwaffe was initially in charge of securing the dropping zones. By telephone, the Luftwaffe received

word from Amsterdam and The Hague of the approach of the planes. Then the SD (Sicherheitspolizei –

Security Service) was informed who turn informed the Dutch leadership. After May 6, security was in the

hands of the Internal Armed Forces.

On Saturday, April 28 – the first British drop had been postponed due to bad weather – a meeting was held

at the exhibition centre. During this meeting the final guidelines were established. This meant, among

others, that the firms Jamin(Crooswijk) and Sillevoet (herbs) made their premises available as storage

places.

Most of the work had to be done by volunteers. These came in large numbers, sometimes perhaps hoping

to get something in return, but mostly to help. It was clear that many these were malnourished. As a

result, they could perform very little. They stood on the sodden field all day to pick up the packages and

pass them on. A long string of people made sure the packages got to the place where they could be

loaded into transport vehicles.

A fairly large part of the food – there is talk of 5 to 10% – ended up in the ditches and the Kralingse Plas.

However, most this food could be saved. The damaged packages were used to alleviate the worst needs.

They were to hospitals, the IKB (Interchurch Office) and other aid agencies.

Fortunately, the number of accidents remained limited, although a few people were seriously injured

when a pair of Lancaster’s dropped their payloads over the Kralinger Hout (part of the Kralingse Bos).

Most accidents were caused by literally cutting one’s fingers on the sharp

edges of the sometimes open cans.

It soon became apparent that the dropped packages were best transported by ship. After the downed

food was collected, it was loaded onto wagons and carts and taken to ships in the Rotte River. About

265,000 packages were taken to Rotterdam in this way. Once again women and men put their shoulders to this heavy work. Under the leadership of Messrs. Binkhorst and Wepster, an amazing feat was accomplished.

Thousands of volunteers lugged the food to berths on the Rechter and Linker Rottekade.

Four more so-called buffer stations were set up on the Linker Rottekade, while a fifth buffer station was located near the Irene bridge on the right side of the Rotte. Thus, the supply of packets could continue while the ships were on their way to deliver their cargo.

All kinds of ships and barges were used for transport by water; even barges from the public works were

used. The disadvantage of the latter vessels, however, lay in their rather large draught, so that they could

not be fully loaded. Twin tugs, “the Twee Gebroeders” and the “Nieuwe Zorg” pulled the barges to their

destinations, such as the factories of Paul C. Kaiser (bakery products), van Nelle and St. Job. In the end, 55

different ships carried 91 barge loads.

One also made sure that the volunteers were fed regularly. Initially the sailors had to make do with

chocolate bars. Later, a quantity of food was set aside and distributed aboard the ships. The sailors could

receive food upon presentation of a consumption voucher.

In the Terbregge dropping area, where the Nieuw Terbregge neighborhood is now located, 3,792,704 tons

of food was dropped. Over all of the western Netherlands, a total of 10,912,859 tons was dropped. At the

site in Terbregge, therefore, a third of all the food was dropped.

After a first day at former Waalhaven airfield on April 29, flights were then carried out at Terbregge on

April 30 May 5 and also in the days after liberation, on May 7 and 8.

Terbregge is therefore for many still remembered as the location where a visible end came to one of the

darkest periods in our history. And it is not only the people of Rotterdam who have fond of this period.

The surviving pilots and other crew members who participated in Operation Manna consider it one of the

most beautiful periods of their lives.

On April 29, 1945, the BBC announced the following during the 12 p.m. newscast:

“As we speak, RAF bombers are taking off from their home bases to food supplies destined for the

starving Dutch in enemy-occupied territory.”

A few residents from Terbregge these drop-offs well.

As a landmark for the pilots, a large cross was made on J. Reijm’s meadow with white sheets. First a

magnesium bomb was thrown on the dropping site, a sign that the dropping would soon follow. The Irene

Bridge was closed and everyone had to get off the streets. At the first drop, packages ended up all

over the place, but things went much better the next time.

“One time I was standing in the meadow and saw the hatches of the low-flying planes open. A torrent of

burlap sacks fell from the sky. I kept looking up, walking backwards, and an instant later tumbled into the

ditch. Oh well, I was willing get wet. It happened that the Germans shot at us from Terbregseweg. A

comrade of mine once got a bag of sugar on his leg. He hurt himself badly.

Only one thing was important: food. There was all sorts of things in it including bags of flour, sugar,

bacon, cigarettes (Chesterfield) and chocolate.

Because of the market gardens, we did not really have food shortages in Terbregge, although towards the

end of the war it began to scarce. Fortunately we were able to help many hungry Rotterdammers. Once

we had tubers from 2% acre of land on the farmyard. Within two hours everything was gone. We divided

it as fairly as possible among the people. They had to pay something for it, but those who didn’t have

money got it in no time.”

“By the CCD (Crisis Control Service) the dropped food packages were collected and taken to the distri-

bution office. In a long chain of men, the packages were passed on.”

Did you know that after a few days the ditches were filled by the many dropped packages; the magnesi-

um rods that were not , after the liberation were beautiful fireworks and as a result the whole surrounding area was illuminated and that, in those days without electricity, was a wonderful spectacle.

Memories

At ten past one on April 29, English Lancasters skim over the ten dropping.places at a height of fifty

meters and below. ‘Nobody is inside anymore,’ writes the then 17-year-old A. de Jong from Vlaardingen

in his diary. Cheering shouts and waving flags, a frenzied crowd watches packets of food fall from the sky.

De Jong now: “That was such a wonderful thing. I lived in a place from which I had a view over the

farmlands as far as Hoek van Holland. There I saw all those packages coming down. A beautiful sight.”

J. Tullener (71) also remembers the drops like yesterday.

As a young man in his twenties, he was on duty with the Food Supply Bureau overseeing the Terbregge

area of Rotterdam. “We had to drag the bags out of the field and from there the food was brought to the

city. It was a delight to see all that food, but you had to remember that all those people in that field were

only thinking about one thing: how am I going to get my stomach full?

One English Portland cement bag contained flour, mashed potatoes, green peas, white beans, bacon,

dried meat, butter and other items rare at the time. Enough for five meals. The Americans dropped

cartons of cigarettes, coffee, tea, cheese, cookies other goodies.

According to Tullener, everyone imagined themselves in lazy land. “To be able to eat cans of corned beef,

something you hadn’t seen, smelled or tasted all through the war, was incredible.”

Tullener: “The Germans only supervised the tarpaulin pilots had to aim the food at, and they picked

up an occasional cookie.”

English navigator John C. (70), a member of 550 squadron is one of the saviours of the starving people. He

carried four drops. A sense of triumph stayed with him: “The contrast with the flights over Germany was

enormous. Those missions had been destructive, this one was not.”

The day of liberation is unforgettable for John C. as well. At North Killingholm airfield, he and his crew

waited for the order to take off: “We did not wait for that order. We took off half an hour early and flew

to Maasdam, outside the dropping site. There we our bags from the hold. The war was over and we

celebrated by making a funny day of it.”

Swedish white bread: It is still thought that the Swedish white bread was thrown out over the

Netherlands by American and British bombers. However, the flour for this bread was brought in by three

huge ships (the HALLAREN, the NOREG and the DAGMAR BRATT) of the Swedish Red Cross, the last two of

which entered the port of Delfzijl on January 28, 1945. The freighter the HAL- LAREN followed shortly

after the other two. Aboard the first two ships were 3,700 tons of food. The HALLAREN contained about

4,000 tons of food. In the Dutch bakeries the real “Swedish white bread” was baked from the supplied

flour.

The problem was that the transport of this bread (under the supervision of the Red Cross) was

hampered by transport difficulties, so that it took the urban population another month to get hold of it.

For the population in the starving areas, the Swedish white bread and a packet of butter was an

unforgettable experience: After years of eating the filthy surrogates and the Government bread made

from potato flour, now, after five years of terror, occupation and starvation, they tasted real bread whose

taste and odor was totally forgotten. To this day, survivors of the hunger winter tell of the food aid, which like a “gift of heaven” from the “sky” for them.

Coby and her mother managed to obtain, besides two Swedish white breads and two packets of butter, a tin of

cookies (which also contained egg powder and milk powder) from a military emergency ration. The

cookies were then made into porridge. Never in all those years had they feasted like they did then!

The men doing this work were from Rotterdam, as many Terbreggenarians had been rounded up and

taken away in raz- zia. The Rotterdammers weak and malnourished. Doctor van Dijk saw to it closely that

they always rested and got half a bar of chocolate. He had hidden his car, a T-Ford, in a barn. He loaded

all kinds of food, to take it to sick and elderly people in the polder.

An inspector from the CCD demanded that he unload it again. Miller Theo v.d. L., a big burly fellow, grabbed the man by his coat, shook him back and forth and said, “What did you have to say, little man?”

With a giant swing, the controller landed in a front yard. “If you don’t make your way out, I’ll wring your neck,” Theo threatened. We never saw the man again. “

“Tk once fished a bag out of the Rotte and put it by the front door. When I returned a little later to pick it up, it was already gone. “

Fifty years ago A short story relayed by Ms. Tol.

During the first days of the food drop it happened quite often, that packages landed next to the demarcated area.

Likewise in the polder behind the Rottekade, famine also prevailed there. From the Rotte river a packet

was seen falling into a ditch. It was decided to wade through the cold water to retrieve the parcel. And so

it happened, they got of the parcel and lugged it through the water to the Rottekade in the house of

painter Chabot. Once there, the package was opened and turned out to contain wheat flour for the most

part.

“Good advice was expensive,” the wheat flour had become wet and thus would start to go bad within

a few days. By mutual agreement, it was decided to divide the flour into equal portions. Mr. Chabot was

appointed to divide this precious property as fairly as possible. He himself did not want to share in this

inheritance. Those present did not agree and assigned a girl to receive it for him.

“Stacked on farm wagons, the packages were taken to the mill ‘De Vier Winden,’ where xe were stored in

the warehouse for the time being, before the food was transported to the distribution stations and the

hospitals. It often lay there too long, because there were too few boats available. I can still see the melted

butter flowing into the water of the Rotte river. A mortal sin. “

“It sometimes happened that a magnesium rod did not ignite. We then set that on fire later. It gave off a sea

of light. I thought all that very well. We were boys of about eighteen at the time.”

After everything was divided fairly, the following day Mr. Chabot organized from the flour obtained, a

pancake party for the youth of the Rottekade .

Not long after, a C.C.D. officer (control service) appeared on the scene to claim the package. After Mr.

Chabot explained that moldy flour could no longer be used by anyone, and was therefore distributed

among those present, the inspector in question nodded approvingly and it was found to be in order. For

acting well and honestly, this righteous man offered Mr. Chabot after five years a real English cigarette.

A short story by L. Dijkxhoorn

With the packet throwing we were in a matt shed between Hoofdweg and Ommoordseweg. After the first drop everyone ran into the country, not counting on the fact that not one but several planes were coming to do their salutary work. With the second load, Toon got a bale of flour on his leg, causing him to fall to the ground groaning and unable to walk. While discussing how to get him home, someone shouted Toon, damn it, here they come again! After which Toon managed to run hard to the barn and was told that his leg was not too bad. T

hat it was not so bad proved later, as Toon sat with his leg on a chair for six

weeks.

Pity

In late April 1945, Mr. and Mrs. Tol went on a family visit in Terbregge to the v.d. family. It was the time of package throwing. Mr. Tol went outside to look and returned a little later with a small dirty skinny boy, which he did not want to let go to Rotterdam alone. A sandwich was prepared, of which he ate only the sausage and fed the rest to the dog. It was decided to take the little boy along and give him a good wash, among other things.

Back home, further investigation revealed that not only he had been taken! In fact, he was covered in lice and fleas.

After the thorough cleaning and pushing the pests to death in the bathtub, the youngster sat down on the

edge of the tub, for he had to “defecate.” After this was arranged and a camp bed was made in order, he

was allowed to spend the night in the Tol house. Already after a few hours the guest became so

nauseated that he vomited all over the place. Namely, what was the case?

He had eaten so much chocolate that his malnourished stomach could not process it (hence the bread to

the dog). In the morning at 7 a.m., Mr. Tol went to the police station to deliver the lodger. Upon seeing

the young friend, the police : “There are again” and to Mr. : “Yes, times a week he is delivered here by

compassionate citizens.”

From the Rotterdams Nieuwsblad of April 27, 1946: The manna of liberation.

Monday next will mark a year since the approaching peace announced itself in a great peace-loving air

offensive. It was then Sunday. At 1 o’clock in the afternoon the air-dropping began. The life-giving manna

fell from heaven.

The morning was full of rumors. Still the Canadians stood in front of the Grebbeline. Liberation was

waiting. Impatience reigned among all and hunger, gnawing hunger. Until around noon the hidden crystal

receivers whispered the message: The planes with food have started. They could be over Holland by one

o’clock.

So still a compromise all Seys Inquart’s denials not withstanding. And they came in long processions.

Wing after wing, squadron after squadron passed low-flying, the coastline. Roaring they traced their

sound trail across Western Holland for the places, where they would drop their rescue cargo.

One knows the days that followed, the air armadas, which returned again and again One knows the

liberating feeling that this war thunder of engines now brought.

Terbregge: It will remain in ‘memory as the place where on the marshy meadow the life-giving food for a

starving people was thrown down from the four-engine giants of our allies.

There, peace was born. There we have been moved and also frenzied with joy. There we stared as if

referred to the forgotten opulence of chocolate, sugar, bacon, etc. There was also a piece of work that

will be remembered.

Terbregge and air-dropping. It has become a household name.

Monday afternoon around noon, seven Lancaster’s will fly low over the Soestdijk palace and drop a

canister at Soesterberg, containing a bouquet of roses, carnations and lilies (orange, red, white and blue)

for the Queen with a personal message from the Marshal of the R.A.F.,Lord Tedder,

An aviation attaché from the British and American embassies, the latter bringing a bouquet and a

message from the United States Army Air Force, will then make their way to Soest- dijk Palace to make

their appearance before the Queen. The planes will fly over Utrecht, Amsterdam, The Hague and

Rotterdam on the return trip to England.

The flags are out!

A monument in memory of Operation Manna in Terbregge

The idea for the realization of a monument to commemorate Operation Manna and in particular the

droppings over Terbregge arose in the mid-nineties. Henk Dijkxhoorn, director of the residents’

organization Terbregge’s Belang, had come into contact with pilots who had themselves in Operation

Manna.

If a new housing estate is built here, none of the residents will realize what miracle took place

here at the end of the Second World War,’ said Dijkxhoorn as he explained his idea in his home on the

edge of what is now New Terbregge.

There is a lot involved in the realization of a monument. Dijkxhoorn had already experienced this with the

of the resistance monument next to the Irenebrug, on the corner of the Bergse Linker Rottekade and

Terbregseweg. Besides the idea, money, inspiration, a network of contacts, a belief in the realization and a lot of perseverance are hard necessities. Fortunately, Dijkxhoorn possesses many of those qualities.

Dijkxhoorn was, among other things because of his honorary chairmanship of the Association Christian

National School Education in Terbregge, his board membership of Terbregge’s Belang and his

commitment to various Terbregge events, no stranger to the part municipal and local authorities.

Together with Bert Wagemans, chairman of Terbregge’s Belang, he managed to bring a committee of

recommendation that included

- HRH Prince Bernhard (+ 2004)

- The ambassadors of America and Great Britain

- Former Defense Minister Joris Voorhoeve- Former Secretary of State R. v.d. Ploeg

- Former member of parliament and city councilor of Rotterdam, F.J. van der Heijden

- Author of, among others, Memories of a Miracle, Hans Onderwater

- Former chairman of the Hillegersberg Schiebrock borough, Ms. Y. Koedam

- Former president of the HillegersbergSchiebroek borough, Ms. M. van Winsen

- Director of property developer Proper-Stokvan Nieuw-Terbregge, Mr. P.v.d. Gugten

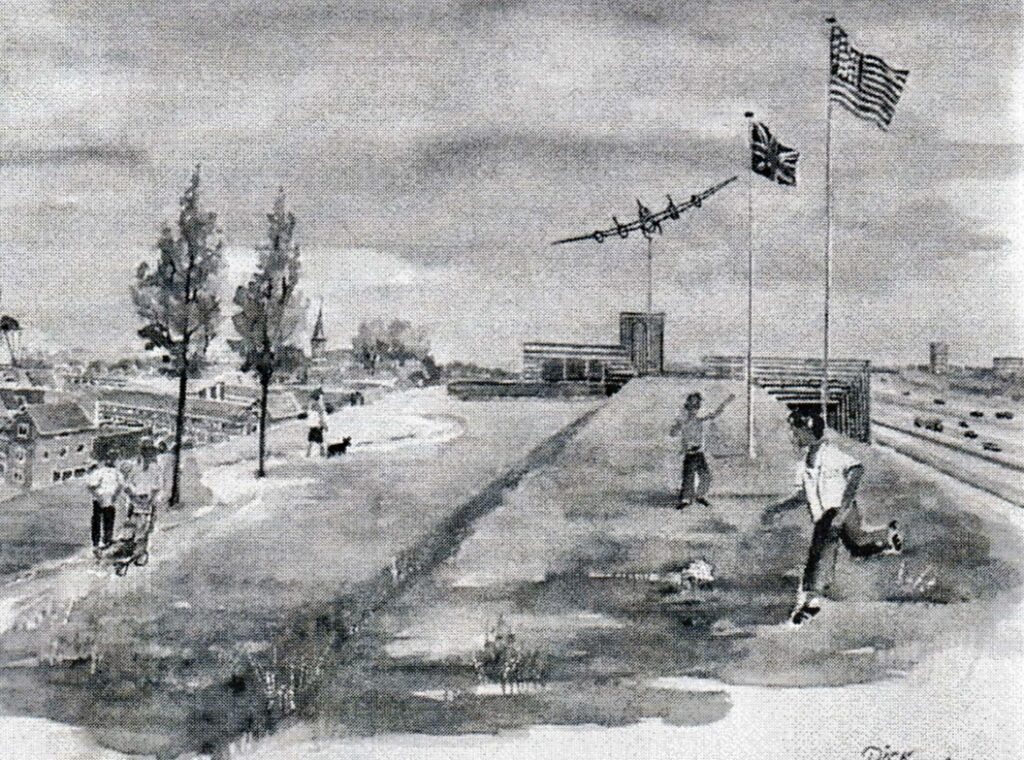

Around 2001, Dick Carlier, artist from Hillegersberg made a watercolor as a design for a monument.

In this watercolor, on the sound barrier near the Observatory, we see a replica of a Lancaster, on a

pole, towering over the surroundings. Because the elaboration of this would attract too much

attention from motorists on the A20 adjacent to the sound barrier, this design did not make it.

René Kombrink, then alderman of Rotterdam responded lukewarmly and reluctantly: Surely Terbregge

already has its monument!

However, Henk Dijkxhoorn did get others enthusiastic about his plans. Things gained momentum when,

during a meeting with the CBK (Center for Visual Arts) and the art group Observatory, consisting of Ruud

Reutelingsperger, Geert van de Camp and Andre Dekker, the idea was born to place the monument in the

Observatory.

This Observatory, developed by the aforementioned artist group above the sound barrier

was in danger of becoming somewhat rundown and future seemed uncertain. The realization of the

monument in this Observatory could kill two birds with one stone:

The cost of the monument could be reduced and there was no need for capital destruction by removing the Observatory.

The artist group created a design for the openwork sculpture of the belly of a Lancaster containing

the representation of food packages. The whole thing was to be worked out in metal.

Meanwhile, the Hillegersgberg-Schiebroek borough had enthusiastically backed the plans.

Schaard and made every effort to make realization of the monument possible.

For the maintenance of the monument, the adjacent elementary school OBS Tuinstad has agreed to

adopt the monument and to clean the site several times a year with their students. In this way, these

pupils can also learn what happened around their school some sixty years ago. Every three months they

renew the viewing boxes placed in the monument.

With a contribution of€ 50,000.00 from Rotterdam Development Corporation and Proper-Stok, half the

money needed was in. In addition, funds contributed, including

- Visser ‘t Hooft Foundation

- The G. Ph. Verhagen Foundation

- Organization of Securities Dealers Foundation- Foundation for the Promotion of Popular Power

- The Van der Mandele Foundation

The CBK the cost of the artists’ fees. Many private individuals also gave, people who had been

eyewitnesses, elderly people from Terbregge, interested Rotterdam- mers and many others who had a

warm heart for the monument.

At a windy gathering on April 28, 2006, the monument was unveiled. Soccer club Sparta had made its

canteen at the complex in Nieuw-Terbregge available to receive the invited guests and a simple gathering

afterwards. Present were among others the American and British Ambassador, the representative of the

Canadian Ambassador, Mayor Ivo Opstelten of Rotterdam, Mr. P. v.d. Gugten of Proper-Stok, residents of

Old- and New-Terbregge, representatives of the media, Hans Onderwater and many other interested

parties. The air force chapel contributed musically to this short ceremony.

The actual unveiling was done by K. v.d. Knaap, State Secretary of Defense together with Ivo Op- stelten

and Henk Dijkxhoorn. It was a memorable moment, also for the municipality of Hillegersberg-Schiebroek,

which for the first time had several dignitaries within its borders. Acting chairman Anton Stapelkamphad

welcomed the guests and the various speakers. Henk Dijkxhoorn took the opportunity to ask Opstelten to

make an effort to honor the name of Air Commodore Geddes by giving his name to the footpath on top

of the sound barrier. It is a request that Opstelten is only too willing to do his best to meet.

The monument to Manna is a , a lasting reminder of a life-saving bombing.

Accountability

The compiler was able to draw on several sources of information for this brochure. He made grateful use

of the well documented books of Barendrecht’s Hans Onderwater: Herinnerin- gen aan een wonder

Operatie Manna

Both books describe the food drops in the Netherlands of April and May 1945. Some portions

of this brochure are almost verbatim from these books.